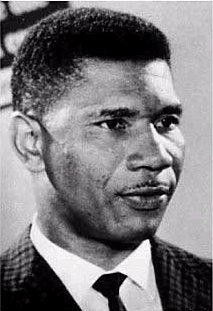

Medgar Wiley Evers (July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963) was an African American civil rights activist from Mississippi.

Early life

He was involved in a boycott campaign against white merchants and was instrumental in eventually desegregating the University of Mississippi when that institution was finally forced to enroll James Meredith in 1962.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Evers found himself the target of a number of threats. His public investigations into the murder of Emmett Till and his vocal support of Clyde Kennard left him vulnerable to attack. On May 28, 1963, a molotov cocktail was thrown into the carport of his home, and five days before his death, he was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from the Jackson NAACP office. Civil rights demonstrations accelerated in Jackson during the first week of June 1963. A local television station granted Evers time for a short speech, his first in Mississippi, where he outlined the goals of the Jackson movement. Following the speech, threats on Evers' life increased.

Assassination

Evers' legacy has been kept alive in a variety of ways. In 1970, Medgar Evers College was established in Brooklyn, New York as part of the City University of New York. In 1983, a made-for-television movie, For Us the Living: The Medgar Evers Story starring Howard Rollins Jr. was aired, celebrating the life and career of Medgar Evers, and on June 28, 1992, he was immortalized in Jackson with a statue.

The 1996 film Ghosts of Mississippi tells the story of the 1994 trial, in which a District Attorney's office prosecutor, Robert Delaughter, successfully retried the case, and won.

Evers' wife, Myrlie, became a noted activist in her own right later in life, eventually serving as chairwoman of the NAACP. Medgar's brother Charles returned to Jackson in July 1963 and served briefly in his slain brother's place. Charles Evers remained involved in Mississippi Civil Rights for years to come. He resides in Jackson.

Children

ChildrenDavid T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, T.R.M. Howard: Pragmatism over Strict Integrationist Ideology in the Mississippi Delta, 1942-1954 in Glenn Feldman, ed., Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South (2004 book), 68-95.

Jonathan Birnbaum and Clarence Taylor, eds. Civil Rights Since 1787: A Reader on the Black Struggle (New York University Press: 2000) ISBN 0-8147-8215-9 (pp. 355-59 (Myrlie Evers with William Peters reprint "Missisissippi Murders"), 522 (Fannie Lou Hamer comment).

Brown, Jennie. Medgar Evers. Los Angeles: Melrose Square Pub. Co., 1994.

John Dittmer, Local People: the Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (1994 book).

Evers, Myrlie B., and William Peters. For Us, the Living. 1st ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967; Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Jackson, James E. At the funeral of Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi: A Tribute in Tears and a Thrust for Freedom. New York: Publisher's New Press, 1963.

Massengill, Reed. Portrait of a Racist: The Man Who Killed Medgar Evers? New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

Nossiter, Adam. Of Long Memory: Mississippi and the Murder of Medgar Evers. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1994; Da Capo Press, 2002.

Charles M. Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (1995 book).

Salter, John R. Jackson, Mississippi: An American Chronicle of Struggle and Schism. Foreword by R. Edwin King, Jr. Hicksville, N.Y.: Exposition Press, 1979.

Remembering Medgar Evers—For a New Generation: A Commemoration. Developed by the Civil Rights Research and Documentation Project, Afro-American Studies Program, The University of Mississippi. Oxford, MS: distributed by Heritage Publications in cooperation with the Mississippi Network for Black History and Heritage, 1988.

Vollers, Maryanne. Ghosts of Mississippi: The Murder of Medgar Evers, The Trials of Byron de la Beckwith, and the Haunting of the New South. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995.

No comments:

Post a Comment