For the film by Peter Brook, see The Mahabharata (1989 film).

The Mahābhārata (Devanagari: महाभारत) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Ramayana.

With more than 74,000 verses, long prose passages, and about 1.8 million words in total, it is one of the longest epic poems in the world. The epic is part of the Hindu itihāsa, literally "that which happened", which includes with the Ramayana and the Purāṇas.

Traditionally, Hindus ascribe the Mahabharata to Vyasa. Due to its immense length, its philological study has a long history of attempts to unravel its historical growth and composition layers. Its earliest layers date back to the late Vedic period and it probably reached its final form in the early Gupta period.

Influence

It is undisputed that the full length of the Mahabharata has accreted over a long period. The Mahabharata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses, the Bharata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Ashvalayana Grhyasutra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. According to the Adi-parva of the Mahabharata (shlokas 81, 101-102), the text was originally 8,800 verses when it was composed by Vyasa and was known as the Jaya (Victory), which later became 24,000 verses in the Bharata recited by Vaisampayana, and finally over 90,000 verses in the Mahabharata recited by Ugrasravas. and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anushasana-parva from MS Spitzer, the oldest surviving Sanskrit philosophical manuscript dated to the first century, that contains among other things a list of the books in the Mahabharata. From this evidence, it is likely that the redaction into 18 books took place in the first century. An alternative division into 20 parvas appears to have co-existed for some time. The division into 100 sub-parvas (mentioned in Mbh. 1.2.70) is older, and most parvas are named after one of their constituent sub-parvas. The Harivamsa consists of the final two of the 100 sub-parvas, and was considered an appendix (khila) to the Mahabharata proper by the redactors of the 18 parvas.

The division into 18 parvas is as follows:

The Adi-parva is dedicated to the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why in spite of this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahabharata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana literature), in particular the Panchavimsha Brahmana which describes the Sarpasattra as originally performed by snakes, among which are snakes named Dhrtarashtra and Janamejaya, two main characters of the Mahabharata's sarpasattra, and Takshaka, the name of a snake also in the Mahabharata. The Shatapatha Brahmana gives an account of an Ashvamedha performed by Janamejaya Parikshita.

According to Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-parva 5) or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions probably correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version corresponds to the oldest, without frame settings, beginning with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The Astika version adds the Sarpasattra and Ashvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, and introduces the name Mahabharata and identifies Vyasa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pancharatrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhishma-parva however appears to imply that this parva may have been edited around the 4th century.

Textual history and organization

For historical context of the tale, see Kingdoms of Ancient India

Some people believe that "The epic's setting certainly has a historical precedent in Vedic India, where the Kuru kingdom was the center of political power in the late 2nd and early 1st millennia BCE. A dynastic conflict of the period could very well have been the inspiration for the Jaya, the core on which the Mahabharata corpus was built, and eventually the climactic battle came to be viewed as an epochal event. Dating this conflict relies almost exclusively on textual materials in the Mahabaharata itself and associated genealogical lists in the later Puranic literature."

Historicity

The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and secular works. It is recited to the King Janamejaya by Vaisampayana, a disciple of Vyasa.

The epic is traditionally ascribed to Vyasa, who is also one of the major dynastic characters within the epic. The first section of the Mahabharata states that it was Ganesha who, at the behest of Vyasa, wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation. Ganesha is said to have agreed to write it only on condition that Vyasa never pause in his recitation. Vyasa agreed, providing that Ganesha took the time to understand what was said before writing it down. This also serves as a popular variation on the stories of how Ganesha's right tusk was broken (a traditional part of Ganesha imagery). This version attributes it to the fact that, in the rush of writing, his pen failed, and he snapped off his tusk as a replacement in order that the transcription not be interrupted.

Structure and authorship

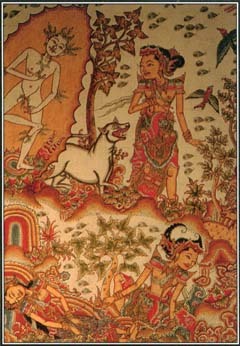

The core story of the work is that of a dynastic struggle for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. The two collateral branches of the family that participate in the struggle are the Kaurava, the elder branch of the family, and the Pandava, the younger branch, with the situation where Kaurava's elder brother Duryodhana is younger than eldest brother of Pandava's i.e. Yudhisthir, leading to conflict where both have the claims to the throne, citing themselves elder.

The struggle culminates in the great battle of Kurukshetra, in which the Pandavas are ultimately victorious. The battle produces complex conflicts of kinship and friendship, instances of family loyalty and duty taking precedence over what is right, as well as the converse.

The Mahabharata itself ends with the death of Krishna, and the subsequent end of his dynasty, and ascent of the Pandava brothers to heaven. It also marks the beginning of the Hindu age of Kali (Kali Yuga), the fourth and final age of mankind, where the great values and noble ideas have crumbled, and man is heading toward the complete dissolution of right action, morality and virtue.

Synopsis

Janamejaya's ancestor Shantanu, the king of Hastinapura has a short-lived marriage with the goddess Ganga and has a son, Devavrata (later to be called Bhishma), who becomes the heir apparent.

Satyavati is the daughter of a fisherman in the kingdom, and she already has a son, Vyasa. Many years later, when the king goes hunting, he see her and asks to marry her. Her father refuses to consent to the marriage unless Shantanu promises to make any future son of Satyavati the king upon his death. To solve the king's dilemma, Devavrata agrees not to take the throne. As the fisherman is not sure about the prince's children honouring the promise, Devavrata also takes a vow of lifelong celibacy to guarantee his father's promise.

Shantanu has two sons by Satyavati, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya. Upon Shantanu's death, Chitrangada becomes king. After his death Vichitravirya rules Hastinapura. In order to arrange the marriage of the young Vichitravirya, Bhishma goes to Kashi for a swayamvara of the three princesses Amba, Ambika and Ambalika. He wins them, and Ambika and Ambalika are married to Vichtravirya.

The elder generations

Vichitravirya died young without any heirs. Satyavati then asked her first son Vyasa to go to Vichitravirya's widows and give them the divine vision of giving birth to son's without losing their chastity. Vyasa fathered the royal children Dhritarashtra, who is born blind, and Pandu, who is born pale. Through a maid of the widows, he also fathers their commoner half-brother Vidura.

Pandu marries twice, to Kunti and Madri. Dhritarashtra is married to Gandhari, who blindfolds herself when she finds she has been married to a blind man. Pandu takes the throne because of Dhritarashtra's blindness. Pandu while out hunting deer, is however cursed that if he engages in a sexual act, he will die. He then retires to the forest along with his two wives, and his brother rules thereafter, despite his blindness.

Pandu's elder queen Kunti however, asks the gods Dharma, Vayu, and Indra for sons, by using a boon granted by Durvasa. She gives birth to three sons Yudhishtira, Bhima, and Arjuna through these gods. Kunti shares her boon with the younger queen Madri, who bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva through the Ashwini twins. However Pandu and Madri, unable to resist temptation, indulge in sex and die in the forest, and Kunti returns to Hastinapura to raise her sons, who are then usually referred to as the Pandava brothers.

Dhritarashtra has a hundred sons through Gandhari, the Kaurava brothers, the eldest being Duryodhana, and the second Dushasana. There is rivalry between the sets of cousins, from their youth and into manhood.

The Pandava and Kaurava princes

Duryodhana plots to get rid of the Pandavas and tries to kill the Pandavas secretly by setting fire to their palace which he had made of lac. However, the Pandavas are warned by their uncle, Vidura, who sends them a miner to dig a tunnel. They are able to escape to safety and go into hiding, but after leaving others behind, whose bodies are mistaken for them. Bhishma goes to the river Ganga to perform the last rites of the people found dead in the burned palace, understood to be Pandavas. Vidura then informs him that the Pandavas are alive and to keep the secret to himself.

Laakshagriha (The House of Wax)

In course of this exile the Pandavas are informed of a swayamvara, a marriage competition, which is taking place for the hand of the Panchala princess Draupadi. The Pandavas enter the competition in disguise as Brahmins. The task is to string a mighty steel bow and shoot a target on the ceiling while looking at its reflection in water below. Most of the princes fail, being unable to lift the bow. Arjuna, however, succeeds. When he returns with his bride, Arjuna goes to his mother, saying, "Mother, I have brought you a present!". Kunti, not noticing the princess, tells Arjuna that whatever he has won must be shared with his brothers. To ensure that their mother never utters a falsehood, the brothers take her as a common wife. In some interpretations, Draupadi alternates months or years with each brother. At this juncture they also meet Krishna, who would become their lifelong ally and guide.

Draupadi

DraupadiAfter the wedding, the Pandava brothers are invited back to Hastinapura. The Kuru family elders and relatives negotiate and broker a split of the kingdom, with the Pandavas obtaining a new territory. Yudhishtira has a new capital built for this territory at Indraprastha. Neither the Pandava nor Kaurava sides are happy with the arrangement however.

Shortly after this, Arjuna marries Subhadra. Yudhishtira wishes to establish his position; he seeks Krishna's advice. Krishna advises him, and after due preparation and the elimination of some opposition, Yudhishthira carries out a Rajasuya Yagna ceremony; he is thus recognised as pre-eminent among kings.

The Pandavas have a new palace built for them, by Maya the Danava. They invite their Kaurava cousins to Indraprastha. Duryodhana walks round the palace, and mistakes a glossy floor for water, and will not step in. After being told of his error, he then sees a pond, and assumes it is not water and falls in. Draupadi laughs at him, and he is humiliated.

Indraprastha

Sakuni, Duryodhana's uncle, now arranges a dice game, playing against Yudhishtira with loaded dice. Yudhishtira loses all his wealth, then his kingdom. He then even gambles his brothers, then his wife, and finally himself, into servitude. The jubilant Kauravas insult the Pandavas in their helpless state and even try to disrobe Draupadi in front of the entire court.

Dhritarashtra, Bhishma, and the other elders are aghast at the situation, and negotiate a compromise. The Pandavas are required to go into exile for 13 years, and for the 13th year must remain hidden. If discovered by the Kauravas, they will be forced into exile for another 12 years.

The dice game

The Pandavas spend twelve years in exile. Many adventures occur during this time. They also prepare alliances for a possible future conflict. They spend their final year in disguise in the court of Virata, and are discovered at or after the end of the year.

At the end of their exile, they try to negotiate a return to Indraprastha. However, this fails, as Duryodhana objects that they were discovered while in hiding, and that no return of their kingdom was agreed. War becomes inevitable.

Exile and return

Modern Interpretations

Modern Interpretations

No comments:

Post a Comment